|

This is the most recent news article by Ryan Dezember of the Mobile Press Register. This is the second article by Ryan about Danny. Great job Ryan! Police rekindle interest in cold case Investigators hope to jog memories of Danny Barter's 1959 disappearance along Perdido Bay Wednesday, July 16, 2008By RYAN DEZEMBERStaff Reporter ROBERTSDALE — With the 50th anniversary of 4-year-old Danny Barter's disappearance approaching, investigators are renewing their interest in one of Baldwin County's most vexing cold cases. On Tuesday, two of Barter's sisters traveled from Texas to Robertsdale, where Baldwin County Sheriff Huey "Hoss" Mack Jr. and one of his top detectives told them and members of the local Rotary Club that local and federal investigators are putting the case back on the front burner. The Sheriff's Office is also pushing to bring national media attention to the unsolved disappearance in hopes of generating leads in the clueless case of a toddler who vanished from the shores of Perdido Bay in 1959. "As we approach the 50th anniversary, it is still likely that Daniel Barter is alive somewhere in the United States not knowing he is Daniel Barter," Mack told the Robertsdale Rotary Club over lunch at Mama Lou's Restaurant. "This is a great mystery in Baldwin County." Mack and Capt. Steve Arthur said that one difficulty in working the case is that there have never been credible leads in the case. "There's no evidence that links this to anything because there is no evidence," Arthur said. About a decade ago, Mack, who was the Sheriff's Office lead detective, said he was asked by then-Sheriff James B. "Jimmy" Johnson to pull the case file on Danny Barter. When he went looking, he found there was none. Nowadays, a missing child case would generate a file that would overwhelm a kitchen table, Mack said. In 1959, however, case files in rural Baldwin County were stored in the heads of detectives, or perhaps on a scrap of paper in a lawman's pocket. As such, the sheriff said, records of Barter's disappearance and the subsequent investigation exist solely in dusty newspaper clippings and the memories of family members, like sisters Wanda McNelly and Theresa White. The story that those clippings tell starts 49 years ago on a Wednesday morning at a campsite on the eastern banks of Perdido Bay. Page 2 of 2 The Barter family — parents Maxine and Paul, four of their six children, an uncle and a cousin — was on vacation, camping on a Lillian-area lot where they planned to one day build a home. At about 9:45 a.m., they noticed Danny was gone. There was no trace of him, not the gray boxer shorts he was wearing, not the Nehi soda bottle he was drinking from, not the footprints his bare feet would have left on the beach had he wandered into the bay. By afternoon, some 150 people were searching on foot, by boat and from the air. There were Baldwin County sheriff's deputies, Foley firefighters, volunteers and enlisted men from Pensacola Naval Air Station. The following day, there were about 500 searchers. The bottom of the bay was dragged; sinkholes and thickets were scoured. On the third day, bloodhounds were brought to the scene. They repeatedly tracked the boy's scent to the same spot on a nearby road. By the weekend, the search grew more grim: Dynamite was tossed into the bay in hopes of jarring a body loose. Alligators were hunted down and gutted, their insides examined for traces of the child. Danny Barter was terrified of water, and so for years many in law enforcement — ruling out an accidental drowning — supposed he was stealthily snatched by an alligator. There were some who thought that he may have been abducted, but aside from the parents' recollection of a peeping Tom in their Mobile neighborhood and a suspicious man at a Lillian grocery store, there was nothing to convince investigators that Barter was kidnapped, Mack said. Today, though, abduction is the prevailing theory, giving Barter's family and investigators hope that the boy who disappeared nearly a half-century ago might turn up somewhere as a grown man with a lot to learn about himself. As such, the Sheriff's Office has started asking around for those who recall the disappearance, looking for new clues to surface. The FBI has become involved, helping local detectives conduct out-of-state interviews, Arthur said. And Mack said there has been a drive to get nationally televised crime shows to take an interest in the case. Even the use of a medium has been contemplated, Arthur said, though costs have so far prevented a psychic from being hired. On Tuesday, Arthur, Mack and Barter's sisters urged their audience to take the story to friends and neighbors, to make the case the talk of the town in hopes of turning up forgotten details. "Time is of the essence; we're not getting any younger," Mack said. "In cases like this it's often the things you don't think are important that turn out to be important." http://www.al.com/news/press-register/inde...ll=3&thispage=1One of the most recent news article about Danny published on June 11, 2008. This article was well written by Tommy Campbell, Publisher of the Choctaw Sun Advocate located in Butler, AL. Danny's mother was from Toxey, AL which is located in Choctaw county, AL. Thanks Tommy! http://choctawsun.com/web/

By Tommy Campbell

Sun-Advocate Publisher

LILLIAN, Ala. — On a hot, muggy south Alabama summer day in June, 1959, Paul and Maxine Barter, four of their six children and two other family members set out from their homes in Mobile on what they thought would be a fun-filled camping trip to nearby Perdido Bay.

Before that ill-fated trip was over, the disappearance without a trace of their 4-1/2 year-old son, Danny, would spark a massive air, land and sea search the likes of which the Gulf Coast had never seen.

Upwards of 2,000 volunteers, including more than 300 sailors and Marines from nearby military bases, law enforcement officials from Alabama and Florida and others using boats, fixed-wing aircraft, helicopters, jeeps, horses and champion bloodhounds combed a five-square mile area in a search that lasted for more than a week before it was finally and reluctantly called off.

The disappearance made headlines in newspapers across the country, and even attracted the attention of FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who sent a personal letter to the family expressing his sadness over the disappearance and assuring them that the matter was being given consideration by the agency.

In spite of the Herculean effort, not one shred of evidence was found to substantiate any of the theories surrounding Danny’s disappearance, which even today, remains shrouded in mystery.

In the 49 years that have passed since the cute little boy with the wavy dark brown hair, dimples, and big, smiling brown eyes disappeared, no remains were ever found, nor have any live sightings been reported.

What happened?

Did he wander away from the campsite and drown in the waters of the Gulf of Mexico, or fall victim to one of the large alligators or poisonous snakes that were known to inhabit the wooded, brushy, beachfront lot?

Or, as his family believes, based on a number of bizarre and still unexplained incidents involving a peeping tom, and mysterious vehicles parked near the family’s home in Mobile and at a store near the campsite on the morning he disappeared, was he kidnapped by someone who had been stalking the family; someone who may have known of plans for the camping trip, or followed them and laid in wait for a chance to grab the child at the site in eastern Baldwin County?

No one knows for sure.

But in spite of nearly five decades of silence, of waiting, hoping, and praying with no new information, his siblings and a “cold case” volunteer who lives in Salem, Ala., remain optimistic that Danny – who would celebrate his 54th birthday on Dec. 12th of this year — could still be alive, or at the very least, if he is deceased, that someone, somewhere has the answers that could give surviving family members closure and peace of mind.

“We are basically everyday people who do detective work on cold cases to try and help law enforcement solve them,” said Lynn Reuss, a volunteer with an organization called Porchlight for the Missing and Unidentified, who first brought the incident to the Sun-Advocate’s attention. “I took an interest in Danny’s case because I am from Alabama and I just have a soft spot for children. He was a very cute little boy. I am hoping that by sharing this information with the home county of Danny’s mother, it will generate some new information to help me with my research.”

It was a letter from Reuss published in the Sun-Advocate earlier this year that generated enough response to cause state and federal investigators to take a fresh look into the disappearance.

A spokesman for the Mobile District Office of the FBI confirmed to the Sun-Advocate on Tuesday that the case has gotten renewed attention from Baldwin County authorities.

Tim White said that while the Baldwin County Sheriff’s Department is the lead investigative agency and has jurisdiction in the case, federal authorities can get involved when local agencies request assistance

“And that is what has happened,” White said. “Baldwin County authorities have asked for our help in conducting interviews and tracking down some people who have moved far away.”

If necessary, he said, the FBI can also assist in conducting forensics tests that are outside of the abilities of local law enforcement agencies to provide.

“We are here to do whatever we can do to help,” White said.

When last seen on the morning of June 17th, 1959, Danny was playing at the campsite, waiting on his parents to finish rigging fishing poles so that they could cast their lines in the shallow waters of Perdido Bay.

According to Danny’s sisters, Wanda McNelly and Theresa White, who now live in Texas, the passing years have not diminished the family’s steadfast hope that their brother could be alive.

“Our parents are both gone now, and we can go and visit their graves,” Theresa told the Sun-Advocate in an interview last week. “We know where they are and what happened to them. But we don’t know for sure what happened to Danny. We can’t go and put flowers on his grave. We believe in our hearts that he is still alive, but even if he isn’t, whatever happened, we would like to know so that we can at least put him to rest in our hearts and minds.”

Digging for facts in the case has been made more difficult by the passing of time and the deaths of family members and investigators who were around at the time.

The family nevertheless clings to the belief that someone, somewhere, knows something about Danny’s disappearance and maybe even his whereabouts today.

“We would love to get a phone call, a letter, anything, just to let us know what happened,” Danny’s oldest sister Wanda told the Sun-Advocate in an interview last week from her home in Texas.

Paul Barter died of a heart attack in 1965 at the age of 46; Maxine passed away 30 years later, in 1995. Their youngest son Tony, who was born in Feb., 1960, died 11 years ago of Hodgkin’s Disease. Unknown to Mr. and Mrs. Barter, Maxine was about one month pregnant with Tony at the time Danny went missing.

Also, as the Sun-Advocate has learned from interviews with family members and investigators, much of the information published in newspaper accounts of the day is inaccurate, and that many of the original investigative reports have either been lost or thrown out in the years since the tragedy occurred.

Theresa, the next-to-the-youngest of the Barter children, was two years old when Danny went missing. She and their brother, Michael, then 3-1/2, did not go on the camping trip but remained in Mobile with their aunt, Vera Barter, the wife of Paul’s brother Jim, who owned the beachfront lot where they were headed.

Wanda, who was just a month away from her 13th birthday, likewise did not accompany the family on the trip, opting instead to spend part of her summer vacation with her widowed grandmother, Rennie (Lester) Thompson at Maxine’s childhood home at Toxey, Ala.

“I found out what had happened when I walked into the kitchen that day and saw my grandmother crying,” Wanda recalled. “I asked her what was wrong, and she said that Danny was missing.”

A native of Michigan, Paul Barter grew up in the Mobile area and enlisted in the U.S. Army. He met his future wife, the former Maxine Thompson, while she was a waitress at a local restaurant. He became a stockroom manager for Morrison’s Cafeteria in Mobile, and the couple and their children settled into a modest but comfortable home on Thrush Drive in the Birdville section of the city.

It was from that residence that Mr. and Mrs. Barter and four of their children, Steve, then 11, Ronald, 10, Bobby, 8, Danny, and their 11-year old cousin, Runeau Barter, loaded up the Paul and Maxine’s station wagon on June 16th, 1959 and headed for the beach.

The trip to Lillian would have taken about an hour under normal conditions, and following what is believed to have been an uneventful journey, the Barters pulled off U.S. 98 onto Boykin Boulevard leading to the property, set up camp and bedded down for the night.

Paul and Jim spent the night in a tent. Maxine Barter, the four boys and their cousin, Runeau, slept in the station wagon.

“It was a camping trip, but they actually went there to help clear the land for a beach house they wanted to build,” Wanda said. “It was a little way back from the beach and there was quite a bit of sand. The water there was shallow, and you could walk a long way out into the bay before it got past your knees.”

That fact, combined with the knowledge that the little boy was scared of the water and wouldn’t go near it unless accompanied by an older sibling or his parents, are two of the main reasons why they do not believe Danny drowned.

The sisters likewise do not believe he would have wandered into the thick, prickly coastal undergrowth that bordered the campsite, and the fact that the little boy was bare-footed, shirt-less and dressed only in a pair of gray shorts on that hot, muggy summer day.

The morning of June 17th began like any other day at the beach for a typical family, the sisters said, recalling what they had been told about the incident.

“You have to understand that neither of us was there, and our parents didn’t talk much about this in front of us when we were growing up because it was upsetting and very hard for them,” Wanda said. Much of what they now know comes from talking with their siblings who were there and who could recall details of the trip.

After awakening that morning, Mrs. Barter, accompanied by Danny and another of the children — whom they believe to have been Ronald — drove to a nearby store in Lillian to buy food for breakfast, some snacks and soft drinks.

News articles of the day indicated that it was Mr. Barter who drove to the store but both sisters said those reports were incorrect. Also, they said, one of those soft drink bottles would later become known as a major “missing piece of the puzzle”.

Arriving back at the campsite, Maxine prepared breakfast while Paul played with the children. Afterward, Danny opened one of the Nehi® soft drinks and was walking around holding the bottle at the time he went missing.

According to a report published in The Pensacola News Journal on June 18th, 1959, Mrs. Barter described her son as a “mommy-daddy baby” who would not stray far away from them. They had promised to take Danny fishing later that morning in the shallow waters of Perdido Bay, and she told the paper that he was standing next to her while she attempted to untangle a line on one of their fishing poles.

Mrs. Barter said that she had put three hooks on lines when she looked up a few minutes later, sometime between 9:30 and 10 a.m., and noticed Danny was gone. After a quick search of the perimeter turned up no trace of Danny, his mother “became desperate” and ran to a nearby house to call for help, according to the newspaper.

That help arrived in the form of scores of volunteers, law enforcement officials, and sailors from Naval Air Station Pensacola and other bases along the Florida and Alabama Gulf Coast. The intense search continued that afternoon and well into the night, and for a week afterward.

Several times over the coming days, searchers formed human chains and walked shoulder-to-shoulder through the shallow waters of the bay and nearby woods but found no sign of the child.

Dr. S.R. Monroe, a Gadsden veterinarian who learned about the search from a newspaper headline, called to offer the use of three of his champion bloodhounds. Baldwin Sheriff Taylor Wilkins gladly accepted the offer and the dogs and their owner were rushed to the scene by Alabama State Troopers.

Dr. Monroe, who is now deceased, spent several days searching the area with the hounds, and stated flatly to the Mobile Press Register on June 21st that, in his opinion, “the child did not leave the scene walking.”

Although news reports of the day made it sound as if the site was overrun by giant, man-eating alligators, poisonous snakes, and quicksand bogs, none of the siblings remember the campsite as being that dangerous.

“I’m sure there were alligators and snakes around,” Theresa said. “But it wasn’t at all like they made it out to be. It was a nice place.”

Sheriff Wilkins told the Press-Register at the time that he did not believe the child was attacked by a ‘gator since Dr. Monroe’s bloodhounds failed to pick up a trail which could have led to the scene of such an attack.

Lillian resident Carl P. Klein, who helped to organize one of the searches, in an article published by the Mobile Press Register on the 25th anniversary of the disappearance in 1986, said that he didn’t put much stock in the alligator theory, either.

“The dogs (Dr. Monroe’s bloodhounds) always came back to that point near the pavement,” Klein said.

He also said he did not believe Danny had wandered away from the site or gotten lost.

“Our mother always said the same thing,” Theresa told the Sun-Advocate.

“As far as we know, he got that far and that was it,” Wanda added.

Although no footprints were found leading toward the bay, Navy divers — on the chance that Danny could have drowned or been snatched by an alligator and dragged to an underwater den — scoured the floor of the bay and set off underwater explosive charges at several deep-water holes in an effort to dislodge a body.

Mrs. Barter said in published reports that one diver assured her that, in his opinion, the boy did not drown.

Several large alligators were shot and gutted to see if any evidence could be found that one of the large reptiles might have eaten the child, but in spite of those efforts, no such evidence was found.

After three days, Sheriff Wilkins likewise said publicly that he was “nearly satisfied that the boy did not wander into the woods or water near the campsite.” Although admitting that authorities could not substantiate a kidnapping since no ransom demand had been received and no one had actually seen Danny being abducted, Wilkins said that he tended to lean in that direction, “since every foot of the land for five miles around and almost as much water has been thoroughly searched without finding a trace of the child.”

The distraught, sedated mother agreed.

“I definitely believe now that someone picked him up and has carried him away,” she told a Press Register reporter at the scene.

“Mother tried to tell them the whole time that she was afraid he had been kidnapped but nobody would listen to her,” Wanda recalled. “You could see the bridge going into Florida from the site. Someone could have grabbed Danny, got on U.S. 98 and been long gone in a couple of hours.”

The kidnapping theory has been bolstered by another seemingly trivial clue that actually could be an important “missing link” to the abduction theory — despite the massive search, no trace of the Nehi® soft drink bottle Danny was holding at the time of his disappearance was found, which leads family members and researchers to discount the theory that he met a violent death in the clutches of an alligator.

If Danny was snatched by a stranger, or if he somehow willingly got into a waiting vehicle, he could have been holding the bottle, family members said.

“If he had been attacked by an alligator, in all likelihood, he would probably have dropped the bottle during the attack,” Reuss told the Sun-Advocate.

And, the sisters agreed, their parents would have no doubt have heard the child screaming or calling for help had an alligator been after him or had he become disoriented and lost.

“There’s no way he could have walked that far away that they couldn’t hear him calling,” Wanda said.

Mrs. Barter said in published reports that she believed someone had walked up the road to the somewhat secluded campsite, unnoticed to anyone there, and grabbed the child.

“You couldn’t see the campsite from the road, you had to go down a long path,” Wanda said. Unknown to the family, a kidnapper could have parked a car nearby and been lying in wait in the thick undergrowth waiting for an opportunity to grab the child.

Mrs. Barter told the Pensacola News Journal at the time that if Danny had indeed been kidnapped, it could not have been for monetary gain.

“I know it wasn’t for ransom, because we have no money saved and are supporting our children on my husband’s income,” she said in the June 21, 1959 article.

In a 25th anniversary article published in 1986 in the Mobile Press Register, former Baldwin Co. Sheriff Wilkins – who at that time was operating a security company in Bay Minette – said that memories of the incident still haunted him.

“You know, we never found the slightest trace of the boy,” he said. “Not one piece of clothing or anything concrete to tell us if he drowned or somebody took him.”

Wilkins added that searchers “didn’t leave anything unturned,” and that while he personally hated to send the people home, after weeks with no trace, he had no choice.

The Pensacola paper reported that a “wake-like” funeral pall seemed to hang over the searchers when they were told it was over.

Even so, the former sheriff slept in his car at the site for three nights after calling off the search just in case Danny might wander back, or that some clue or other evidence would be found.

One report, publicized in the June 25th edition of the Pensacola News Journal, claimed that a Lillian resident reported to Sheriff Wilkins’ office that — several days after Danny went missing — persons in a car on the main road of the community were seen to let a small boy, about Danny’s age, out of the vehicle and pull away. The witness said the boy ran off after the car but if any other details were ever provided, or if the incident was investigated further, it was not reported to the public or to the family.

Wilkins died in 2002.

About a month after the disappearance, Paul Barter’s employer, Morrison’s Restaurant, obtained the services of investigator Edward J. Foster, of New Orleans-based Pendleton Detectives Inc., to conduct an independent investigation. The results of that investigation were never shared with Baldwin County officials nor made available to the family.

The Sun-Advocate contacted the Pendleton organization, which is now located in Jackson, Miss., in an attempt to obtain a copy of the report. Officials at the present company said that the New Orleans office was sold to Vinson Security Service in 1963. Vinson still operates in New Orleans but did not respond to a Sun-Advocate email asking if records from 1959 still exist.

In a series of what family members say appeared to have been unrelated incidents at the time, those separate occurrences now seem to lend more credence to the theory that their brother may have indeed been kidnapped, both sisters told this newspaper.

About a month before Danny’s disappearance, Maxine Barter was hanging out her washing on the clothesline in their yard when she noticed a strange man parked in a car on the street in front of their home on Thrush Drive.

There were a lot of young girls who lived in the neighborhood at the time, and Mrs. Barter was afraid it might be a possible attempt to kidnap one of their two daughters or someone else’s.

“When mother started walking toward him he put a newspaper up to hide his face,” Wanda recalled. “As she got closer, he drove away.”

Not long afterward, a neighbor saw a “Peeping Tom” standing looking into the window of the Barter boys’ bedroom one evening.

The brothers, including Danny, were sleeping on bunk beds in the room at the time.

“Our neighbor had a German shepherd that ran around to the side of our house, barking,” Wanda said. When the neighbor came to get dog, she saw the man and ran to tell Mrs. Barter.

By the time they could get around the house, the unidentified intruder had fled, but left several clearly defined footprints in the soil underneath the window.

The Mobile Police Department supposedly made plaster casts and photos of the prints but Sun-Advocate calls to that department asking for information on the old records were not returned.

Another incident, which may have not gotten the attention it deserved at the time, was at the Lillian store which Mrs. Barter and the two boys visited on the morning of June 17, 1959.

Danny and one of his brothers remained in the car while Mrs. Barter went inside. A car driven by an unknown man pulled up beside the Barter’s vehicle, and the driver sat staring intently at the two boys before driving away from the store. It made such an impression on Danny’s older brother that he reported the incident to his mother when she came back to the station wagon.

“As far as we know, the man didn’t bother them, just looked at them,” Wanda said.

If Baldwin or Mobile County officials still have any of the records, members of the family say they would love to see those documents.

Several months after Danny disappeared, Mrs. Barter wearied of people riding by staring and pointing to their house.

“Every time she would go to the store, someone would bring it up,” Theresa said. “She finally got tired of the whispers and couldn’t take it anymore and told daddy she wanted a new house, just to try and get away from some of that.”

Mr. Barter was approved for a VA-backed loan and so they moved into a new home on Mobile’s Dog River.

Some time later, they moved back to a rental house in the Birdville neighborhood.

“It was a real emotional struggle for both Mother and Daddy,” Theresa recalled. “They had a hard time dealing with Danny’s disappearance.”

In 1962, their grandmother, Rennie Jackson Thompson, invited them to come and live in a home their uncle had built, so the family packed up and moved to Choctaw County.

“I worked at the shirt factory in Toxey and mother worked at Vanity Fair in Butler,” Wanda said. “Daddy got a cook’s job on a boat out of Louisiana, so he was gone a lot.”

Later, one of their mother’s sisters, who lived in Corpus Christie, Texas, became seriously ill and after a trip west to help care for her, Maxine and family decided to move there in 1963.

“We all stayed pretty close and we’ve been here ever since,” Theresa said.

Family members have not sat idly by through the years, but have worked in any way they can to keep Danny’s story in the public eye.

They have even contributed samples of their own DNA to a national database for missing persons so that any evidence that turns up can be tested to determine if it is in fact, Danny’s.

“So far, we have heard nothing, but that doesn’t mean we don’t have hope,” Wanda said. “There is always hope.”

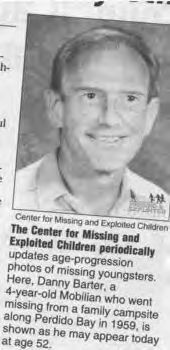

Danny is listed on the website for the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, which has provided the family with an age-progressed computer image of what he would look like today as a man in his mid-50’s.

An independent website featuring photos, scans of various newspaper articles through the years, and other information has been set up at www.littleboylost-dannybarter.1colony.com.

Family members say that somewhere out there today they believe Danny is still alive, but simply does not know his true identity.

“If he is alive, Danny has a couple of distinguishing scars,” Wanda said. Among those are:

n Marks where he fell and bit all the way through his tongue; and,

n Scars on his fingers where he accidentally stuck his hand into a fan as a baby.

Meantime, both the family and Reuss say they intend to keep on searching, asking questions, and keeping the faith that one day they will have a definitive answer to the nearly five-decades-old question of what happened to Danny Barter.

“We are planning to have a candlelight vigil for Danny in June, 2009 at Perdido Bay, where Danny went missing,” Reuss said. “It will be the 50th anniversary and we hope the media attention from that will get it national coverage.”

Maternal uncles and aunts of the child in Choctaw County, Ala., would have included J.B. and Dorothy Hatfield and C.L. and Zeola Thompson.

“It’s been so long that it seems like most people just don’t care anymore,” Wanda said. “We will never give up caring, or hoping, that one day Danny will be found alive or else we will find out what really happened to him.”

Persons who have any information that might be helpful in solving this case are asked to contact Baldwin Co. Sheriff Huey “Hoss” Mack at 251-937-0210; the Mobile District FBI office at 251-438-3674; The National Center for Missing and Exploited Children at 800-843-5678 (800-THE-LOST), www.ncmec.org; or Lynn Reuss at Lhreuss1972@hotmail.com, or 334-759-0356.

A news article was done about Daniel on December 24, 2006. It was printed in the Mobile Press-Register. Cold case remains warm for missing boy's family

Sunday, December 24, 2006

By RYAN DEZEMBER

Staff Reporter

On a Wednesday morning in June 47 years ago, Daniel Barter, six months shy of his 5th birthday, vanished along the banks of Perdido Bay.

In the days that followed, Danny, as he was known to his family, became the subject of one of the most intense searches in Baldwin County's history.

The manhunt included several hundred volunteers and emergency personnel, the U.S. Navy, a trio of prize-winning bloodhounds, helicopters, skin divers, mounted posses and even hunters who stalked alligators and sliced open their bellies searching for signs of the 3-foot-tall boy from Mobile.

In the years since Danny disappeared from his family's Lillian-area campsite, relatives have waited fruitlessly for answers.

"My parents are both buried but I know where, I can visit the cemetery," said Theresa White of Victoria, Texas, who wasn't yet 2 at the time of her brother's disappearance. "With Danny, we just don't know."

Said Wanda McNelly of Fort Worth, Texas, who was 8 when her baby brother went missing: "We don't care if it's bad or good news, we just want to know after all these years."

Neither McNelly nor White were on hand when the boy disappeared from the easternmost area of Baldwin County on June 17, 1959. The older sister was staying with her grandmother, who lived about 100 miles north of Lillian. The younger sister, not that she would have remembered anything, had been sent back to Mobile with relatives and another young brother, Michael, the day before.

At the bayside campsite, according to family members and news reports, were the boy's parents, Maxine and Paul Barter; three brothers, Steve, Ronald and Bobby; an uncle and two cousins.

The Barter siblings' recollections of Danny's disappearance are hazy.

"I guess it's one of those type deals where you don't remember things you don't want to remember," Bobby Barter, 56, who now lives near Corpus Christi, Texas, said in an interview.

Also, many of those involved in the search for Danny have died. But the episode was well documented by the Press-Register. From those reports, a narrative of the disappearance and subsequent manhunt develops.

It was just about 9:45 a.m. and the Barters were preparing equipment for a fishing trip when they realized Danny was gone. About 15 minutes had passed since his brothers had last seen him near the campsite's small beach. He had spent the night in his uncle's car with the other children and he was barefoot, still wearing the gray boxer shorts he slept in.

The search for Danny started at the beach, a few miles north of the U.S. 98 bridge into Florida. Danny didn't like the water, and there were no footprints leading into the bay.

By the afternoon about 150 people were scouring the secluded and swampy area, looking for a brown-haired, brown-eyed boy. There were state highway patrol officers from both states, Baldwin County sheriff's deputies, conservation officers, Foley firefighters, about 55 enlisted men from Pensacola Naval Air Station and volunteers.

The search was called off at dark that day, but family members were hopeful because Navy pilots had said that no body had surfaced on the bay.

The next day participation in the manhunt grew to about 500, including 270 enlisted men. The search focused on five square miles around the campsite. While mounted deputies from Escambia County, Fla., and Baldwin County combed higher, less-dense woods, bands of 25 men walked shoulder-to-shoulder through Lillian Swamp searching sink holes and thickets. On the bay, about a dozen boats dragged nets along the bottom.

On the third day, a Gadsden veterinarian arrived with three champion bloodhounds to track Danny Barter's scent.

"These bloodhounds can pick up a scent, even in the water, up to two weeks old, and the only places they have trailed the child is where he was known to have been prior to the disappearance," the vet, Dr. S.R. Munroe, told reporters after a day of unsuccessful searching.

With the weekend came doubts that the boy was alive. The massive search wound down and those who remained turned to more grim endeavors.

They tossed dynamite into pockets of deep water, hoping to jar the boy's body loose if it were lodged below at depths invisible to divers. Baldwin County Sheriff Taylor Wilkins Sr., who led the search, ordered rescuers to track down large alligators.

Two gators -- one 5 feet long, the other 4 -- were caught and gutted but no remains were found. Still, there were reports of a 10-footer in the area, and an attack by an alligator remained a viable theory.

At home in Mobile, sedated by doctors, 34-year-old Maxine Barter told a reporter in a Saturday interview that she was sure her son was kidnapped: "I hope now that someone did take Danny because I know if anyone wanted him bad enough to kidnap him they would take good care of him."

The case remained open for years, but no leads ever emerged. Paul Barter's employers, Morrison's Cafeteria, even hired the Pendleton Detectives Agency, but the family never received any report from the New Orleans sleuths.

The FBI eventually got involved and the family, which had a contact in Washington, even received a telegram from Director J. Edgar Hoover, pledging that the bureau would look into the matter, White said.

Of all the cases Wilkins handled in his 28 years as sheriff, the disappearance of Danny Barter was one he could never break. Wilkins died in 2002.

"It liked to have driven my daddy crazy," said Taylor "Red" Wilkins Jr., a Bay Minette lawyer. "I don't believe it was a case, I think an alligator got that baby."

Unlike Wilkins Jr. and others who have weighed in over the years, the Barters have long dismissed the alligator theory and cling to the idea that someone stole Danny Barter to keep him as their own.

"We've never thought anything else except that he's alive somewhere," McNelly said.

After the disappearance, Maxine Barter told her daughters about a string of incidents occurring before Danny disappeared that involved shady figures lurking around the Barters' Thrush Drive home in Mobile. Once, the sisters said, a peeping Tom was nearly caught staring into Danny's bedroom window.

At 4½, Danny Barter was at an age that makes it tough to profile a possible abductor, said Charles Pickett, a senior case manager for the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

"If you have a parent that lost a child they want someone younger so it can truly be their own," said Pickett, who has been involved in the Danny Barter case for 22 years. "With pedophilia, you're usually looking for someone older."

Pickett said the breadth of the search for Danny Barter, going so far as to bomb the bay and eviscerate alligators, was unheard of in those days, particularly in such a rural area. It's unfair to wonder if today's technology would have discovered the boy, Pickett said, but it's certain that if a little boy vanished from a campsite nowadays, the story would be national news.

Even if it didn't draw national news cameras, Danny Barter's disappearance was a big enough story in Mobile to linger for years. By 1963, the Barters had decided to move to Texas, where they all still reside.

"Mother said she was just tired of people gawking and riding past the house," McNelly said. "We needed a new start."

Paul Barter, who had worked for Morrison's in Mobile as a stock room manager, started his own diner outside Fort Worth, Texas, before dying of a heart attack in 1965. Raising the family by herself from then on, Maxine Barter died in 1995.

"We always hoped that before Mother passed away that we would have an ending," Bobby Barter said. "But it never happened."

Every so often someone might call family members claiming to have some information or a recollection or a theory, but, White said, everything always turns out to be a dead end.

Occasionally, White said, she'll contact the FBI hoping to track down a file, or she'll check in with Pickett or request an updated age-progression photo of her long-lost brother.

And she and McNelly keep in touch with Lynn Reuss, an Opelika-based volunteer for Porchlight International, which is a sort of clearinghouse for data on unsolved missing and unidentified persons cases that date back as far as 1920.

White even sent the Center for Missing and Exploited Children some of her DNA should bones that may be Danny's ever turn up.

"Whatever the deal is, we just want to know," White said. "He's a missing piece of us." The image below is the newest age-progressed photo provided by the NCMEC

|

|